The problem with compartmentalisation

What should I do if efficiency morphs into alienation?

We live in a world that rewards efficiency and productivity. We give ourselves a slap on the back when we can portion up our day into twenty neat tasks (including, maybe, “send partner loving text”), and then tick them all off triumphantly before falling asleep (with our smartwatches tracking our progress through the night).

This dividing up of life, though, can be a form of avoidance - known in psychological circles as “compartmentalisation”. Compartmentalisation is the isolation of various of one’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs or roles from each other, especially when they are contradictory.

We all need to compartmentalise sometimes…

We all do it in some form or another. The classic example is the way passionate dog and cat lovers can compartmentalise off some animals as companions, and others as suitable food. Think also of the lifelong socialist who can’t face the local comprehensive, and chooses to send their child to private school instead.

We also mostly operate this way when we combine demanding jobs with a home life. We try to wall off the stresses and conflicts of work from our time at home, where we attempt to refocus onto our partner and family.

What does compartmentalisation really mean?

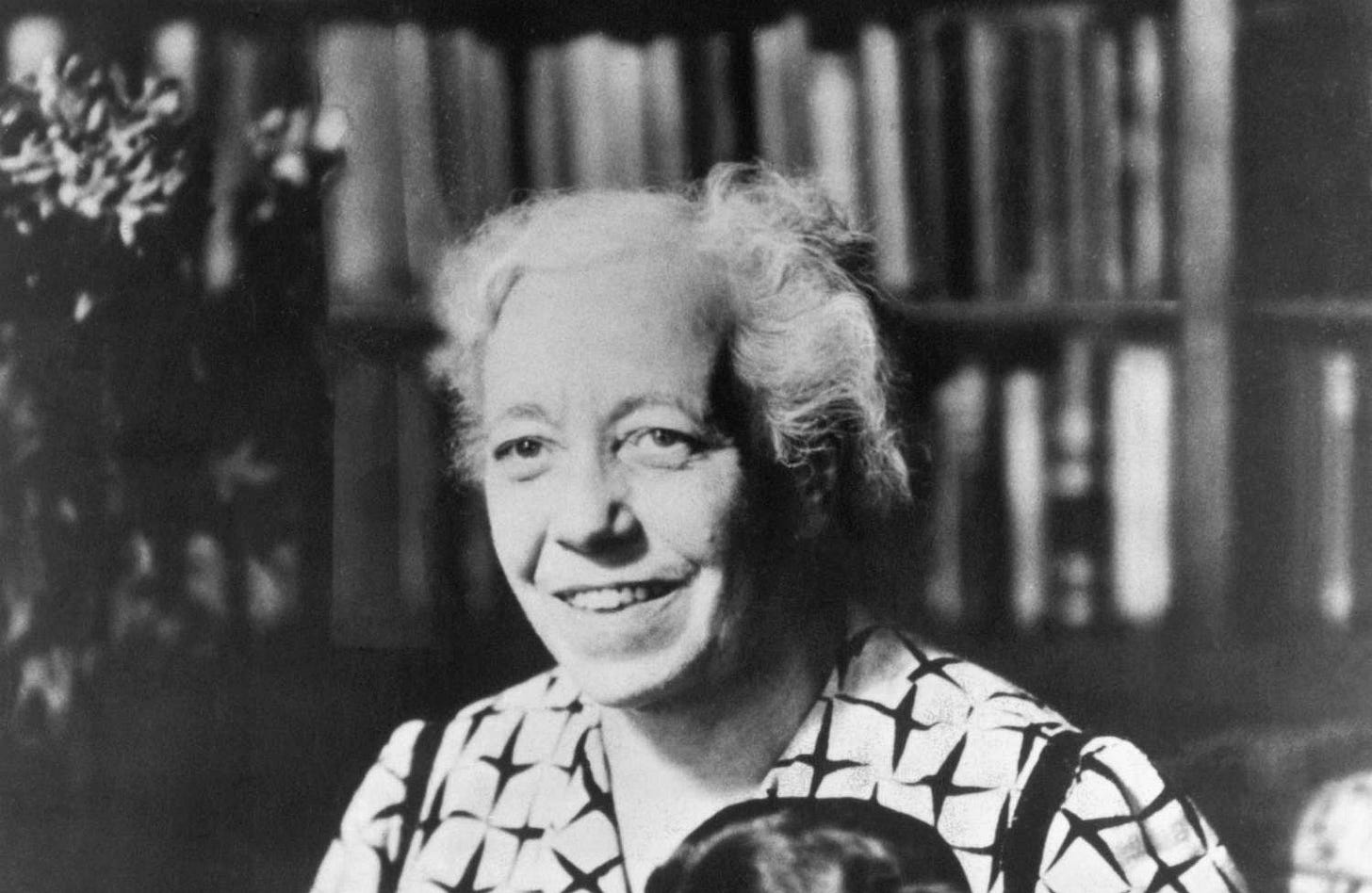

The term was coined by Karen Horney, a neo-Freudian who emigrated to America in the 1930s and became both dean and founder of the American Institute for Psychology.

While Freud stressed instinctive drives, Horney put equal emphasis on societal pressures. She believed that compartmentalisation is a successful defence against the tension and anxiety of incompatible beliefs, excessive use of compartments can leave people feeling disconnected and alienated.

Solutions

So is compartmentalisation something to be embraced, as a way of coping with an increasingly complex world, or is it the root of much of our modern angst?

Without separate compartments for work and home, it is tempting to fire off the occasional text during dinner in a restaurant, or to quickly check emails before bed.

How else would anyone navigate the complex relationships in the office, where someone can be your boss and your after-hours tennis or drinking buddy?

To succeed we do need to be flexible, to put things aside and to move on.

BUT - the person who found themselves lauded and promoted by the world for their ability to compartmentalise with extreme efficiency may well find issues when they settle into a long-term relationship.

Compartmentalisation can be a nightmare when it comes to love. Is it even possible to fall in love with someone who schedules you into small parcels of their life? With many of the couples I counsel, one half feels the other is shutting them out, and some question if they really know their partner at all.

If you’d like to build your communication toolkit and ensure your connection stays strong, I recommend my book The Happy Couple’s Handbook.

Creating a fresh compartment can sometimes temporarily ease a problem - for example if your partner hates your mother, rows can be avoided by visiting her alone.

However in the long term, the walls just create more tension, misunderstanding and divided loyalties. Under stress, compartmentalisers tend to be very rational: ‘I can’t solve that problem, so why lose sleep over it?’, or ‘how can we move on, if you are forever obsessed with the past?’ The greater the problem, the higher the walls, and the more the couple become stuck.

How can a couple get past compartmentalisation?

If this sounds familiar, how can you integrate your life more or encourage your partner to have a less rigid divide?

Start with the ‘what kind of day did you have?’ conversation. Instead of the usual one-sentence answer, ask supplementary questions so you can properly understand the personalities and the issues. You might meet some resistance, but persevere. With sustained interest, everyone will unwind and talk about their work. This conversation will also help you read each other better and not mistake a bad mood at the beginning of the evening for a reaction to something you did.

If there are occasional opportunities to socialise with your partner’s colleagues, use them, at the very least collect your partner after their work to put a face to the names.

With internal family issues, for example with children from a previous relationship, try getting everyone in the same room at the same time. Often in compartmentalised lives, the person in the middle is having separate conversations to broker peace but just ends up being pulled in every direction.

In the short term, the atmosphere will be uncomfortable - but everyone should resist the temptation to storm out. This will just reinforce the compartments. If you can all stay with the difficult feelings, you will be amazed at how quickly solutions emerge.

Much of the success of couple and family counselling is not due to the skill of the therapist, but that everyone is stuck in one room together and encouraged to keep talking.

The walls between different compartments are nearly always sustained by rationalising. When an issue arises, instead of becoming bogged down with the practical details ask yourself: how am I feeling?

When communicating the answer, don’t blame your partner. For example:‘I am angry,’ is better than‘ you make me angry’, which will just raise the temperature.

Next instead of focusing on the solution, allow time for both of you to feel understood and completely heard. Normally a compromise will emerge out of the discussion. Finally, look fora way forward that is built around taking a joint responsibility.

To be honest, integrating our lives and in particular our beliefs is difficult - after all we all like a little wiggle room.

However, beware of compartmentalisation. It can leave you trying to be all things to all people and ultimately left asking: so who am I?

As always, if it feels like the right time to start marital therapy, send an email to Tricia (tricia@andrewgmarshall.com) or use this contact form for a virtual or in-person appointment with one of my team of therapists in London, or with me here in Berlin.

With love,

Andrew

Love this post and the nuance of it and compartmentalisation.

It reminded me of this quote

If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?

Hillel the Elder, circa 50BCE